$ Identity Capital $

Freddie Wulf reflects on neoliberalism in the arts and the current pressure to capitalise on identity as an artist.

- - -

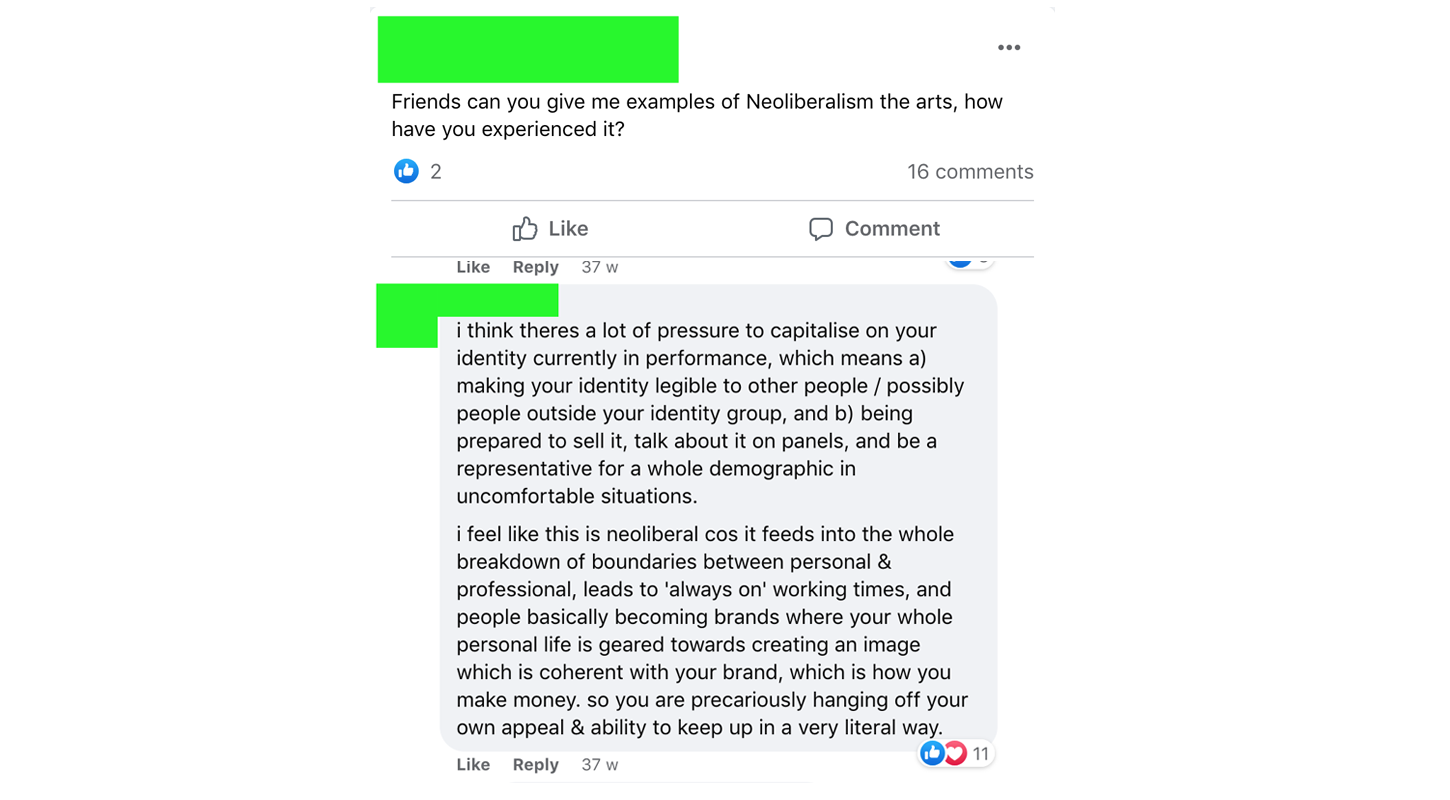

This article is based on a Facebook comment I made about neoliberalism in the arts and the current pressure to capitalise on identity as an artist:

My perspective here was based on the challenges of working as a performer, while navigating changes in the way I understood my own identity - and the experiences I've seen/heard from people around me.

In the last 10 years I've seen the trend for categorising art by identity grow, in a way which both creates opportunities, and applies unmanageable pressure to artists who hold marginalised identities. It feels important to create real space for this discussion, so I’ve spoken with four artists connected to Trinity whose practice is also affected by these issues.

- - -

I find 'neoliberalism' a sprawling, confusing word so I asked my friend Phoebe (an academic) to define it:

Neoliberalism is a form of capitalism which 'is about individualising and commodifying all aspects of human experience'* causing people to function as brands/consumers, in competition with each other - and breaking down community support structures.

- - -

Yewande Adeniran (aka Ifeoluwa) frames the context:

“Capitalism is all around us. Even in our so-called liberal arts spaces, we're always bound by the economic system that we live and die by. When you're a marginalised person always feeling the full weight of the oppressive system on top of you, there's an added pressure to sell parts of your identity.

“When it concerns Blackness, we are [so] used to hearing about the trauma of Black people that when a Black artist tries to present something new - outside of this - it's often met with hesitation and, more often than not, will not be commissioned. Wider society's insistence on traumatic work serves the purpose to keep us within the space we occupy within the social hierarchy. If we're always making art about trauma, that trauma becomes our whole selves – we become it. Once we step outside of this, we become free."

- - -

Tom Marshman also highlights the expectation for traumatic narratives to be front and centre:

“I have observed audiences craving queer artists' trauma, and when the performance created is more joyous and celebratory, they're left wanting. But my experience isn't all about oppression and sometimes I just want to make work that is frothy and light.

I see artists around me be flippant with 'heavy life shit’, as a deliberate mechanism for dealing with the way queer people can often be wheeled out to tell our stories. My research into queer histories has seen queer people deal with this aspect of our lives with humour and wit, and that has been the case for a very long time.”

- - -

Katayoun Jalilipour is changing the way they work to navigate these structures:

“I made a decision to stop accepting opportunities that are identity-based – and that’s been an interesting challenge. It blurs your sense of self, so you don’t know what people are interested in.

I’ve become more interested in not having my face and my body in the work. There's this thing that happens with commodifying your identity - you become like the object, the desirable object or the interesting part - because you’re queer in the literal sense of the word. I don’t want to be the selling point of my work.

You can feel a bit trapped, especially if you’re trans. It makes it more difficult to allow space for changes."

- - -

My experience was about coming out to myself as trans while working as a performer - and feeling unable to work, in a period where I couldn't define myself:

"I felt a pressure to know who I was and write it down in words and commit to it, in order to continue working.

I was having this magical experience in cabaret spaces, finally feeling a sense of belonging and opening up to who I was. But outside of those spaces the pressure to define myself, and the need to avoid speaking for a group I didn't know if I was part of, became too much.

I was often sidestepping and navigating what I could do to earn money without being disingenuous – while trying extremely hard to figure my identity out. Eventually I quit art and performance altogether."

- - -

Ania Varez is finding ways to take a break from the art / identity dynamic, while continuing their practice:

“Disclosing that I come from a humanitarian crisis and making work about it made me ‘urgent’. I wanted to talk about it, but suddenly that very personal desire became a brand worth capitalising on. But what if I wanted to talk about anything else?

Now I’m taking a break and focusing on the creativity that exists outside this contract, trying to remember why I love making art. It’s hard to have energy for it because I must earn my living from other jobs instead. What if we valued those personal acts of creativity? Whose voices would be celebrated and what could those voices change? I want more attention placed on those acts of creativity that will not make it to the market.”

- - -

I'm now coming back to performance, and a lot has changed in the four years since I last worked as an artist. I’m really glad that there’s more space for artwork by people with marginalised identities, and more openness to discuss the structural barriers – access budgets are a game changer! But as the industry goes on this learning process, and deals with cuts to funding, I think there's a tension between offering more opportunities and offering good, workable opportunities with adequate support.**

I want to advocate for institutions to take the pressure off individuals – both artists and staff members who hold marginalised identities – to represent whole groups. And for proper resources to be put in place to support people when they are doing work which crosses between the personal and professional, or which takes those experiences outside of their own communities. And – what I've learnt more than anything from the artists in this article – is to value the work in itself, and to value all the work, not just the parts where people are speaking directly about their identity.

*'Neoliberalism' definition by Phoebe Patey-Ferguson

**There is much more to be said on this point. For an off-the-top-of-my-head list of some ideas for how to make opportunities more accessible and beneficial for artists, see my blog.

For a more detailed discussion of identity in art practice, with a deeper discussion of the meanings of individual and community identity and 'neoliberalism', see: The White Pube podcast

This piece was commissioned by Trinity as part of our ongoing commitment to supporting creative communities. The piece has been supported by the Cultural Recovery Fund. This article was published on 15th November 2022