Opinion: Voting matters

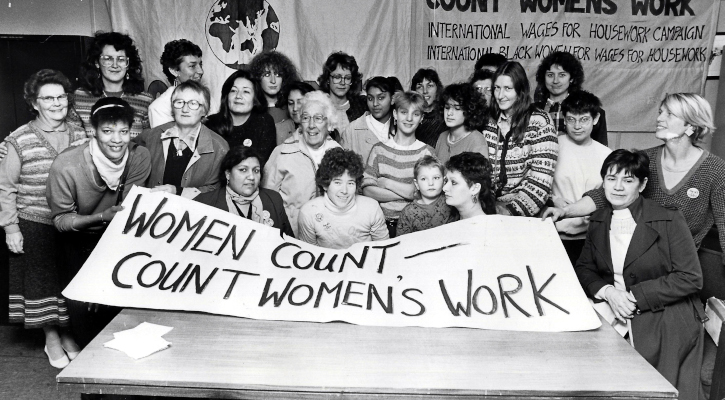

1985 Oct 25 International Time Off for Women Day, credit Evening Post, collected as part of Art of Resistance

Trinity is committed to creating ways in which citizens can take an active role in shaping arts and culture. In 2025 Our Citizens Assembly for Culture, created, in partnership with St Pauls Carnival and Citizens in Power will take place, offering people living in the West of England Combined Authority region the opportunity to actively shape the arts and cultural experiences that matter most to them and their communities.

As part of this commitment we are connecting with leading voices in the cultural sector to ask them to share their thoughts on the different civic and democratic tools that we as citizens can access. In the first in our series of opinion pieces exploring civic participation Dr Edson Burton, Curator at Trinity, reflects on the role of voting in democratic decision making.

"The Bristol Bus Boycott, the Gay Rights Movement, the Disability Rights Movements of the 1960s-1990s. These campaigns or movements have led to legislative changes that have, in turn, transformed our social attitudes"

Opinion: Voting Matters, Dr Edson Burton

‘Politics time again, are you gonna vote now?’ lamented the reformed Buju Banton, alluding to the lethal elections of his native Jamaica. But the question could equally be applied to the forthcoming British election. During the last General Election (2019), 67% of the population voted, up from the all-time low of just over 59% in 2001.

While that figure is on the rise, it still means that over 30% of the population has no say in how they are governed. According to a recent YouGov poll, the reasons given for not voting include a lack of access to polling stations, ineligibility, and no forms of ID. However, the most prominent reasons are a lack of trust in politicians and a feeling that voting will make little difference.

One might argue that cynicism is rife in politics, with pledges that are misleading if not downright dishonest. It has ever been thus, but in a crowded information world, voters may become so confused as to become indifferent.

Perhaps the dance of truth owes as much to us as to our politicians. Few would jump for joy at the thought of higher taxes, but without increased taxation, how can we fund our troubled public services, invest in green technology, or ensure education offers opportunities for all?

Responding to concerns over national identity, political parties offer a raft of immigration control measures that, if implemented, would lead to a national staffing crisis. Yet, to extol the virtues of immigration is to risk electoral suicide.

The convergence between the main political parties may also fuel voter apathy. "There's no difference between them" is the often-heard lament. Despite the barbs and bites, there appears, at times, to be more that unites than divides the main parties. They vie to expose the actual commitment to an agreed-upon agenda rather than the agenda itself.

But it is worth remembering that this consensus is the result of political participation. The impetus to secure or woo working-class votes in this election is a result of the extension of the franchise beyond a small property-owning class. Once enfranchised, all parties have had to take seriously the interests of a wider range of citizens with divergent interests and lives. Further franchise expansion was not some benign gift of a ruling class but the result of blood and guts campaigns by working-class men and women. Think Chartists, Unions, the Suffragettes.

What is the point of voting if you cannot meaningfully participate in society? If your race meant you could be legally denied access to jobs or employment? If your gender meant you were denied promotion, let alone equal pay? If your sexuality or sexual identity could lead to your imprisonment?

Such was the case prior to major civil rights campaigns: the Bristol Bus Boycott, the Gay Rights Movement, the Disability Rights Movements of the 1960s-1990s. These campaigns or movements have led to legislative changes that have, in turn, transformed our social attitudes.

Broadly speaking, all our political parties have arrived at baseline of inclusivity consensus. In recognition of new voting demographics and the reputational damage of appearing to be illiberal parties may wish to appear to be race, gender, and disability friendly

But how safe is this consensus? Is it a pragmatic concession to the present while some hanker for an illiberal past? The USA has recently demonstrated the danger of complacency as civil rights advances have been eroded by reactionary forces. Could the same thing happen in England? Perhaps if it is electorally beneficial, but certainly not if it is electorally damaging. It could only be so if we vote or hint that our vote is for the preservation of our rights.

Beyond preserving our rights, further changes that we want to see in society will inevitably involve legislation, which in turn will involve exerting pressure upon politicians. The time scale of change may not suit the urgency of our demands, but rather than lose heart, we must continue to exert political pressure through campaigning and ultimately through the ballot.

Not voting is a verdict on politics, but it cannot lead to change; rather, it will maintain the status quo. In the calculus of win or lose, only voters and their interest's matter.

Vote.

Find out more about movements that have shaped society by exploring our interactive heritage timelines